This site may not work properly using older versions of Edge and Internet Explorer. You should upgrade your browser to the latest Chrome, Firefox, Edge, Safari, or any other modern browser of your choice. Click here for more information.

Your Stories

This is where we tell your stories, cover topical issues and promote meaningful initiatives.

Report calls for Aboriginal-led care to be funded, backed and heard

A new report, spurred by the continuing failure of successive Australian governments to close the health gap, puts Aboriginal-led primary healthcare organisations squarely at the centre of real and lasting change.

But it also points to barriers to change: the stubborn structural racism embedded in political, media and bureaucratic systems, and an ongoing refusal to reckon with the legacy of colonisation in this country.

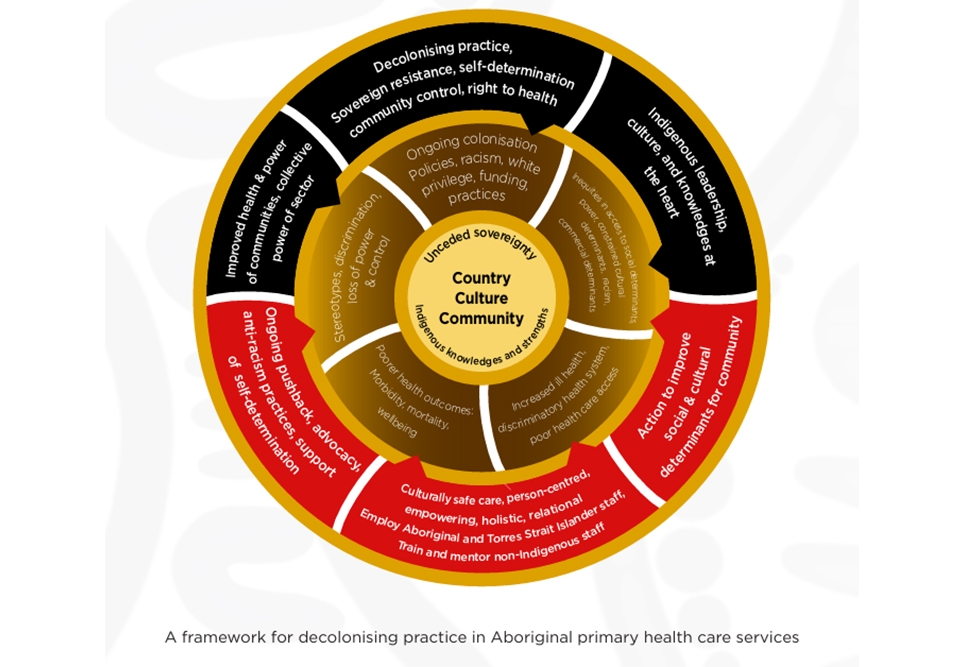

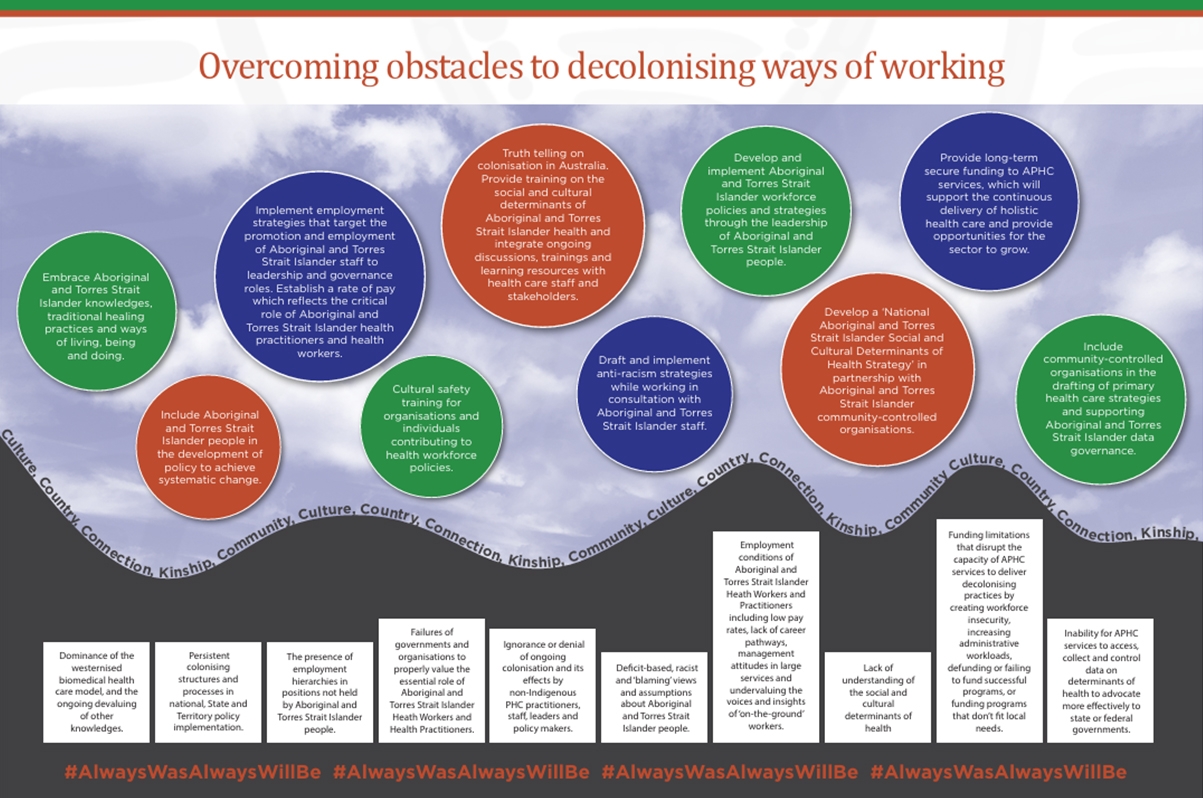

A striking visual from the report, Decolonise Now: Community-led pathways to decolonising practice in health (2018 – 2024), makes it plain. Above the line: a vibrant vision of justice – First Peoples-led care, flexible funding, cultural authority, anti-racist systems, and strong community voices. Below the line: the status quo – fixed, short-term funding, white-led governance, racist assumptions and deficit based thinking dressed up as policy.

“Unless governments, services and funders actively reverse those bottom-line realities, they’re not neutral – they’re upholding colonised practice,” says Dr Toby Freeman, Associate Professor at the University of Adelaide and one of the report’s chief investigators.

Dr Freeman notes the deep disappointment that followed the rejection of the 2023 referendum for a constitutionally enshrined Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

“Australian governments must now work directly with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders and communities to support decolonising ways of working,” he says.

The report draws on seven years of collaboration between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers and non-Indigenous researchers from the University of Adelaide, Flinders University, University of Technology Sydney, University of Queensland and the University of British Columbia.

It documents case studies from five Aboriginal Primary Health Care organisations across the country, each offering powerful, practical examples of how colonised health systems can be challenged – and changed.

At Central Australian Aboriginal Congress in Alice Springs, community-led alcohol policy reform slashed emergency department presentations and domestic violence rates, despite opposition from government and industry.

In Darwin, Danila Dilba Health Service delivers holistic, in-home support to mothers and families, building long-term relationships based on trust, cultural understanding and respect.

Inala Indigenous Health Service in Brisbane, though government-run, has created a culturally safe hub where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people can access care without the fear, judgment or barriers they often face in mainstream hospitals.

In Adelaide, the Southern Adelaide Local Health Network’s Aboriginal Family Clinic navigates within mainstream systems to deliver as much culturally safe care as it can – but struggles persist due to governance models that still limit Aboriginal leadership and autonomy.

And in Nowra, Waminda South Coast Women’s Health and Wellbeing Aboriginal Corporation throws out hierarchical management models entirely, replacing them with a shared Aboriginal leadership team and embedding cultural knowledge, ceremony and sovereignty into every part of its work.

The report makes the case that no model of decolonised care is sustainable without a strong Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workforce – particularly in leadership, advocacy and decision-making roles.

It also calls for a shift away from deficit-based narratives — those familiar tropes about “what’s wrong” with Aboriginal health — to strength-based stories that recognise what is already working and why.

Dr Freeman says, “Practices and attitudes have improved – but not fast enough. Aboriginal-led organisations and their advocates have had to fight for years for recognition and funding. They’re used to struggle – they’ve always had to battle for change. They’ve never been handed the reins easily.”

“I believe people in positions of power know Aboriginal-led practice is better. But systemic racism is hard to shift – that baked-in belief that white experts know best, that white intervention is the answer.”

He says the report should serve as a roadmap for both community-controlled and government-managed services, as well as for policymakers and funders who are serious about structural change.

“Our hope is that this report contributes to the urgent and crucial project of decolonisation – not just in health, but across all sectors.”

“The call is clear: back Aboriginal-led care with long-term, flexible policies – or be complicit in repeating the same failures.”

Access the Decolonise Now: Community-led pathways to decolonising practice in health (2018 – 2024) report here.