This site may not work properly using older versions of Edge and Internet Explorer. You should upgrade your browser to the latest Chrome, Firefox, Edge, Safari, or any other modern browser of your choice. Click here for more information.

Your Stories

This is where we tell your stories, cover topical issues and promote meaningful initiatives.

Remote communities are tracking climate from the ground up

Citizen science is at the heart of a new research project helping remote desert communities prepare for, and respond to, increasingly extreme weather. The project draws on Aboriginal people's traditional knowledge and lived experience of environmental change, as well as insights from remote nurses who see first-hand how extreme weather affects health and workloads. Local agencies and services will also be involved from the start, with goal of creating community-lef, achievalbe solutions tailored to each place.

Climate Preparedness in Very Remote Desert Communities is a five-year project funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and led by Associate Professor Supriya Mathew (Remote Health Systems and Climate Change Centre, Menzies School of Health Research), an environmental health researcher based in Mpartnwe (Alice Springs). It builds on her previous work in some of the regions hardest hit by environmental change.

“Much of Australia’s climate health research has focused on urban and temperate zones,” says Dr Mathew. “But the challenges in desert Australia are different – and so are the solutions. You can’t just copy and paste.”

Remote health workers are central to the project, Dr Mathew says, because of their long-standing relationships with community members.

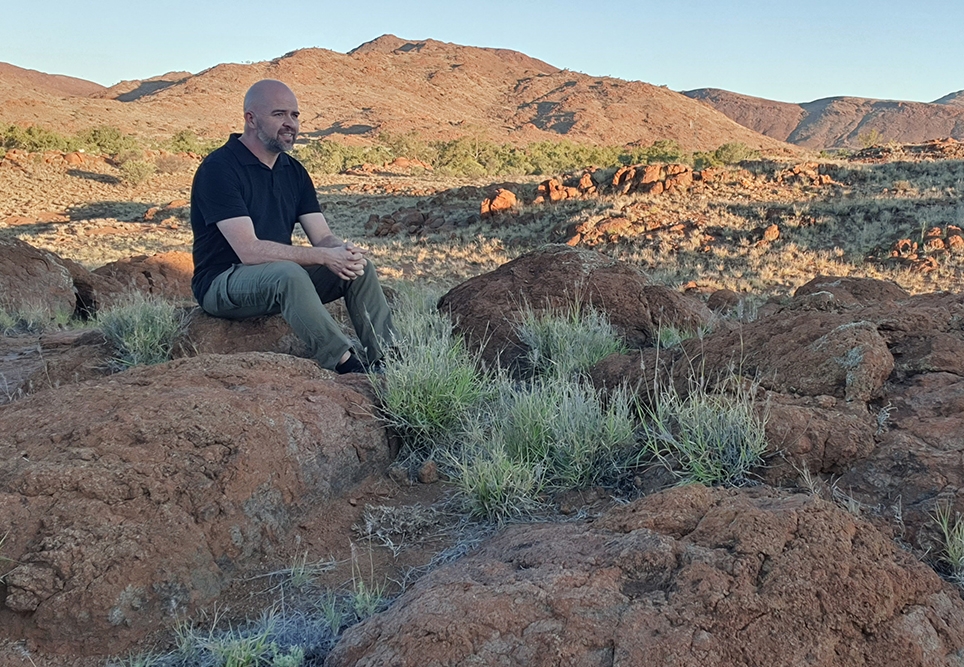

Associate Professor Jamie Ranse, an investigator on this project, is a nurse clinician-academic. He works as an academic at Griffith University on the Gold Coast, and as a locum community nurse in a very remote desert community of South Australia.

Retaining nurses in remote areas is important, says Dr Ranse. “There is a large amount of agency or locum nurses who practice in very remote desert communities. Understanding health workforce patterns, relating to willingness to work during extreme weather events in remote communities, is important.

“This research may help inform workforce models that provide consistent staffing to priority populations and help retain nurses in remote desert communities.”

Dr Ranse and Dr Mathew both point to the importance of data collection and environmental monitoring.

Dr Ranse says, “We already know climate affects health – but in remote areas, we don’t have the data. After a bushfire, flood or extreme weather event, we don’t have enough information about how people respond, how it affects their health in the long term. In urban areas, we track things like heatrelated hospital admissions in real time. That level of data just doesn’t exist out here.”

Environmental monitoring is a major gap, Dr Mathew says. “In remote regions, we don’t routinely measure air or water quality, or track how heatwaves or cold snaps affect temperatures inside homes,” she says. “In cities, during a bushfire, you get real-time air quality alerts sent to your phone. That doesn’t happen in remote Australia. There’s no monitoring system – and often no monitoring equipment.”

That’s where citizen science comes in.

“If we want better data, we need to work with local people. With training, community members can collect information and help build a more complete picture of what’s happening – and help develop strategies on how to better respond.”

Rather than researchers arriving with their own agenda, the project will begin by asking each community what matters most to them.

“It might be water quality, or housing, or bushfire danger,” Dr Mathew says.

“Some communities might be worried about food security or soil health. Our job is to listen first, then support people to collect the evidence they need to push for change.”

Dr Mathew gives the example of water testing: “A community worried about water quality might learn how to take a sample and send it to us. Later, they might feel confident to share that data with a government agency. That confidence – to ask questions, to demand answers – that’s a sign of success.”

Already, changes are happening. In earlier projects, some remote area nurses said they have adapted the clinic opening hours to suit the weather – opening earlier during summer heatwaves, or later on freezing winter mornings. The change reduces after-hours callouts and works better for community members, too.

Good climate communication and health promotion has also come through strongly in previous focus groups with remote PHC staff.

“Sometimes people won’t drink the water available in a community. That might be a trust issue,” Dr Mathew says. “Maybe key local agencies are monitoring it, but they may not be reporting it back to the community. Or maybe the water is safe but is hard water and has an unpleasant taste. The solution could be as simple as filtering it and bottling it for drinking – but you need that conversation first.”

There’s also growing recognition, she says, that Western science and Aboriginal people’s knowledge need to work hand in hand.

“A lot of information is shared. There’s genuine effort across the country – people are realising it’s not productive to rely only on Western science. As researchers, you’re not there all the time. Aboriginal people are. They have deep knowledge of place – we have to find ways to use both.”

For Dr Mathew, real success will be when local people have the tools to integrate knowledge, and confidence to lead local climate responses.

“If people have the information, the training, and the opportunity to lead – they will,” she says. “And when they do, things start to shift.”