Lyn’s achievements as a remote health professional are shared between clinical care and governance.

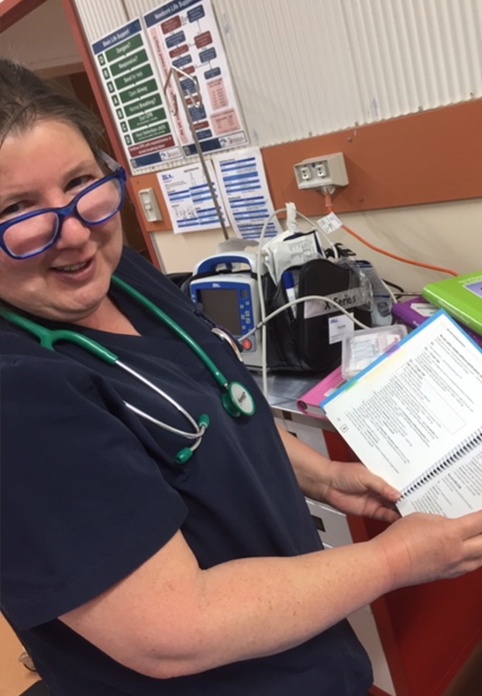

With a stethoscope in one hand and a strategy document in the other, Lyn works as a Clinical Nurse Consultant for Nganampa Health Council as a rostered clinician, educator, and quality improvement consultant across six clinics.

On top of this role, she facilitates CRANAplus courses and was a longstanding CRANAplus Board Member prior her decision not to stand for re-election in October.

She represented CRANAplus on the National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce and chairs the Editorial Committee for the Remote Primary Health Care Manuals.

“Those manuals are embedded in both government and Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services,” Lyn says.

“Their content is translated to health systems and embedded in them. They’re used as a reference point when looking at cases and determining the approach, and used as teaching manuals – even overseas. I’m really proud to have been able to contribute.”

Lifelong development

An endorsed nurse practitioner, Lyn’s commitment to improving the structures supporting remote health is fuelled by a wealth of hands-on experience, which she’s still accumulating.

She recalls the value of working in the adult and paediatric wards of Alice Springs hospital prior to heading to Docker River in 2001. “It gave me a chance to understand the population catchment area,” she says.

“I could work out ways to communicate with people who didn’t have English as a first language, gain cultural awareness, and talk to people about local matters.

“I could see the conditions that were being admitted – and it was so valuable to have done paediatric work. When you work remote, you have to expect at least a third of the population is going to be under 25 years old.”

As she headed further out, Lyn found herself working in conditions conducive to personal and professional growth.

“Remote area care is the most collaborative work you can possibly do, and you can learn so much from your colleagues,” she says.

“When we didn’t have as much equipment, and were using things like radio, it was harder to talk to someone and run things past them. Now, it’s about collaborative care. It’s easier [than ever] to contact a colleague, specialist, doctor, or another nurse.

“In some ways you’re going to be scrutinised a lot more when remote. Often there’s another nurse or medical student with you to learn something, and often there’s family members.

“All of that means you can learn and do so much more than you can in other conditions.”

Memorable moments

Reflecting on career moments that have stuck with her, Lyn remembers the early days when babies were born in the bush, and she was the only health professional present.

“My husband would be in the clinic too as he had to warm up the blankets to be ready for the new baby,” she says.

“And the grandmother would be there, and my heart would be in my mouth, and I’d be praying, because there was no way of evacuating them. Where I was there was no night airstrip.

“I had three [babies] a year for a number of years, born out there… I wasn’t planning that, but some of [the mums] were!

“When everything went well, and they stayed in the clinic… After, they’d go home to their place, and I’d go have a sleep. I’d see them in the afternoon and make sure all was well. That was really affirming, to see that.

“This other lady used to come in for a specific needle once a month,” Lyn continues.

“I weighed her, and she’d lost a lot of weight… I looked at the notes. She’d been steadily losing weight for months.

“I asked her, are you walking? – because she used to walk. She said ‘no, no, I’m not walking, I don’t feel very well. I can’t feel like walking.’ I had a closer look.

“When I made her lie on the bed, so I could see her tummy, it wasn’t a matter of feeling this unusual lump, I could see it sticking out. I’m having a meltdown inside – thinking, she’s going to go, and I’ll never see her again.

“I brought her sister in and said, ‘I think you need to go to Alice Spring for investigation’.”

Six weeks later, the lady reappeared back in community and came in to see Lyn.

“I said ‘What you are doing? Are you alright?’” Lyn recounts, still a little disbelieving of the transformational impact of her health check. The lady’s visit to a major hospital had enabled the complete surgical removal of her cancer. “She said, ‘They took that rubbish out, sister. I feel better!’,” Lyn says.

Embedding culture in care

Lyn’s believes RANs should aim to respect culture rather than enforce a strictly biomedical perspective, because trust is key to improving health outcomes. She recalls the days prior to Purple House, when community members had to receive dialysis in Alice Springs.

“They’d go to Alice Springs and quite often get lonely, and come back to community,” Lyn says. “I used to say, ‘you come and tell me if you are in community.’ … People would leave dialysis, but at least they would come and tell me. Then we could work out a plan.

“There was one lady that left dialysis; there was a really important funeral. I said, ‘Right, how can we work this out to give you a couple of days?’”

Lyn talked to the dialysis unit and worked together with the client to take measures to keep her healthy until the funeral in three days’ time, using resources available locally. Despite their best efforts, the lady’s health deteriorated without dialysis.

“The way funerals worked in that community… The body was in Alice Springs, and the charter plane would bring it out on the morning of the funeral,” Lyn says.

“This poor lady got so unwell that she said she has to go back to town… We were on the airstrip waiting for RFDS, when the charter plane came in with the coffin.

“She just couldn’t wait any longer… so she went in on the plane and had a good outcome. But I felt so sorry for her because she got so close. We were all crossing our fingers and hoping she’d get to the funeral. It just didn’t quite work out. But she was grateful that we tried.”

It’s a sad story – Lyn has many happier stories to tell – but it does reflect the importance of local care, the potential impact of health inequity on cultural practices, and the need for health practitioners to factor in the cultural needs of clients.

One of many

Despite her achievements, Lyn remains humble, and far from complacent.

“I was walking around Alice Springs hospital once with a colleague, looking for a patient,” she says in an illustrative anecdote.

“My colleague says, ‘Oh goodness, it’s like walking around with the Queen. Everyone is waving and saying hello to you.’

“I said, I don’t know if that’s a good thing. There are too many people in hospital that I know.

“It was really nice to be acknowledged [with the Aurora Award], but a lot of people do an awful lot of work out remote,” Lyn says in closing.

“We all contribute, in all sorts of ways.”