Professor Sue Kildea’s remote midwifery career commenced in the 90s and ultimately led to her 11-year tenure as CRANAplus’ Vice President. More recently, she spent a perspective-shifting decade in the largest maternity facility in Australia.

“I’ve returned to remote Australia, near Alice Springs,” Prof. Kildea says, “and I cannot believe the state of remote area maternity services, and mothers’ and babies’ health.”

The state of remote maternity services

“20 to 25 years ago, they thought it would be safer for women to have their babies in the big city hospitals where you’ve got paediatricians and obstetricians, theatres and blood banks,” Prof. Kildea says.

“There’s quite a lot of recognition now that we went too far.

“We should’ve kept many of the smaller maternity units open so that healthy women could stay in their communities and, I think, only removed women out if they had risk factors and needed more intensive and specialised care.”

This mindset ultimately led to the closure of rural and remote maternity units and an exodus of midwives and GP obstetricians. First Nations women increasingly had to receive care in cities, even when low risk and for their first child. Families became excluded from births – one of the most joyous things in life.

“We sent a lot of [pregnant] women who didn’t speak English away,” Prof. Kildea says. “A lot of the time they [didn’t] have an escort and it was really problematic.

“Women don’t like going to the cities. They don’t feel safe; they’re frightened, alone. This hasn’t changed.”

The corresponding gap in health outcomes is well documented. There’s a lack of resident midwives in remote communities where, at the same time, we are seeing some of the highest rates of preterm birth in the country.

“In Australia rates [of preterm birth] might be around 7 per cent every year,” Prof. Kildea says. “They’re 12 to 14 per cent for Aboriginal women. In some of the remote areas, that figure is between 15 and 22 per cent.”

This, in turn, correlates with increased vulnerability to chronic disease.

“I’m not saying all women across Australia can have a local maternity service in their small remote community,” Prof. Kildea acknowledges.

“But there are many remote communities that have over 1000 people in them, and more than 20 women having a baby every year. And they’ve got no resident midwife. That’s just insane.”

Implementing a Birthing on Country model

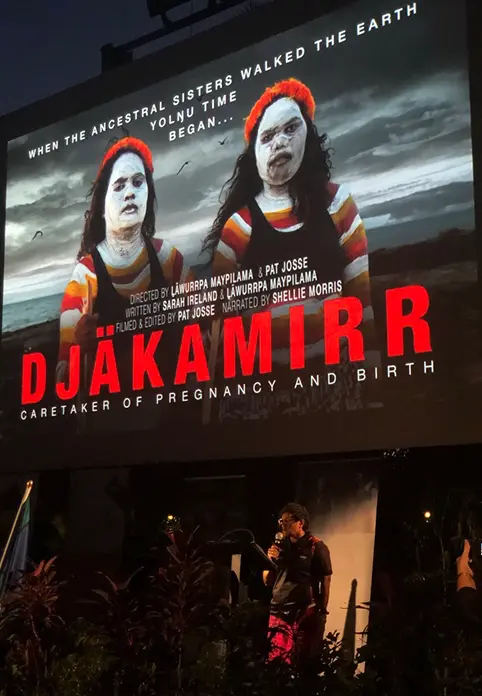

Prof. Kildea, with Professor Yvette Roe, is currently co-leading several projects to change this including the National Health and Medical Research Council’s five-year, $1.5 million project ‘To Be Born Upon a Pandanus Mat’, and the Djäkamirr (Yolŋu childbirth companions) four-year $6.1 million project funded by the Department of Health.

These projects are underpinned by multiagency partnerships and a Steering Committee with representatives from: Charles Darwin University (CDU), Miwatj Aboriginal Health Corporation, Yalu Aboriginal Organisation, Australian Red Cross, Careflight, the Australian Doula College and the Northern Territory (NT) Department of Health, the Australian Government Department of Health (Indigenous Health Division).

The Yalu Aboriginal Corporation Women’s Backbone Committee, comprising of senior Yolŋu women representing the diverse clans in Galiwin’ku, provide leadership and cultural authority.

Together they are aspiring to increase continuity and quality of care by redesigning maternity services on Galiwin’ku, the northeast Arnhem Land island with a population of around 2500.

The goal is to reduce risk factors associated with preterm birth, strengthen midwifery care, and integrate early medical and allied health referral as required.

This includes pairing “named midwives” with pregnant women throughout their journey, and ensuring midwives are recruited and supported to stay and be available 24/7.

They will work side-by-side with the Djäkamirr, who will be embedded in the service to provide clinically and culturally exceptional care. A Djäkamirr is a Yolŋu woman trained and employed to provide guidance and support to a woman during pregnancy, childbirth and until baby turns two years old.

“At the moment, care is dislocated [throughout a woman’s journey, which may be from] multiple providers with little continuity of carer,” Prof. Kildea says.

“We want each pregnant woman to have a named Djäkamirr, who will go with her, providing the continuity of care that the midwife can’t, because the midwife stays in the community.

“We’ve got a very Western medical model out there in our communities, and almost no midwives. We are all missing out on all that incredible knowledge the Indigenous women have had passed down from 60,000 years of Birthing on Country.”

Positive early signs

The results of Birthing on Country implementation in an urban setting have been exceptional, says Prof. Kildea, referring to the successes of the Birthing in Our Community Service in South East Queensland as published in The Lancet.

“We saw a 38 per cent reduction in preterm birth,” Prof. Kildea says.

“We saw women come earlier in pregnancy, and more often. They felt culturally safe – and a lot of that is to do with the First Nations workforce.

“Birthing on County services are also driving changes to the social determinants of health with the emphasis on employment and education of Aboriginal women in these services.

“Women were also more likely to breastfeed, we saw fewer elective C-sections, fewer women having epidural pain relief in labour (less intervention in birth), more physiological birth of the placenta and a reduction in neonatal nursery.”

“Reducing preterm and increasing breastfeeding are two of the most powerful things we can do in the early days to reduce the risk of chronic diseases down the track.”

Prof. Kildea’s research team has also received a Medical Research Future Fund of $5 million to work with communities to test their RISE Implementation Framework in a rural (Nowra, NSW), a remote (Alice Springs) and very remote (Galiwin’ku) site.

The RISE Framework has four pillars to drive reform: (1) Redesign the health service; (2) Invest in the workforce; (3) Strengthen families; and (4) Embed First Nations community governance and control.

References

- Effect of a Birthing on Country service redesign on maternal and neonatal health outcomes for First Nations Australians: a prospective, non-randomised, interventional trial, Prof Sue Kildea et al, The Lancet

- Implementing Birthing on Country services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families: RISE Framework, Prof Sue Kildea et al, Women and Birth