This site may not work properly using older versions of Edge and Internet Explorer. You should upgrade your browser to the latest Chrome, Firefox, Edge, Safari, or any other modern browser of your choice. Click here for more information.

Your Stories

This is where we tell your stories, cover topical issues and promote meaningful initiatives.

60 years a nurse in rural New South Wales

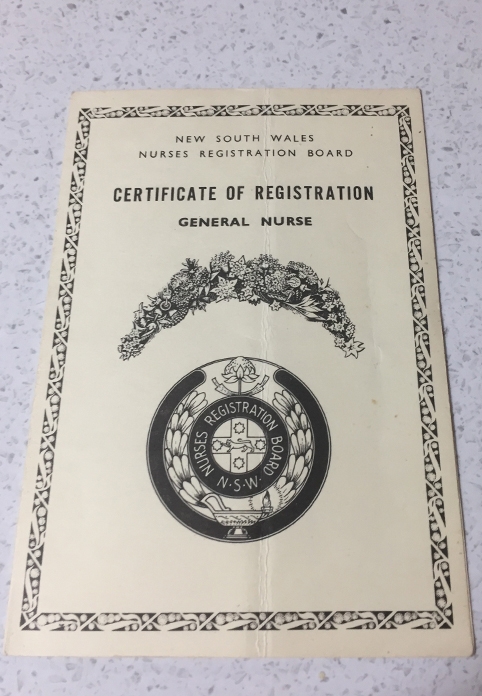

CRANAplus Member Sandra Vicary retired recently, having just reached the milestone of 60 years of nursing in rural New South Wales. She remembers asking permission to marry as a young nursing sister, caring for one of Australia’s first kidney transplant patients, and working through the “Y2K” scare.

Inspired by a visit to a bush nursing post arranged by her school, Sandra walked into her small local hospital on 16 January, 1963 and interviewed successfully for a role as a cadet nurse. She was 16.

“We wore a cap that confined all your hair,” Sandra remembers, “The uniform had short sleeves, navy and white stripes with a large white collar and cuffs, black stockings and black or brown shoes, of a particular leather. Around the waist was a very heavy starched belt, held together with a buckle of two silver pieces.”

When she turned 17, Sandra commenced as a trainee nurse. Each year a star was added to your cap, or a button to your uniform, to mark your progress.

“You went to a Preliminary Training School in six-week blocks and lived in the quarters,” Sandra recalls, “and every day they taught you things like temperatures, pulses, taking a blood pressure, bathing a patient. Then you went back to the ward.”

During her fourth year, Sandra gained experience at the “Coast Hospital” – Prince Henry Hospital at Little Bay, Sydney. She recalls the hyperbaric chamber for treatment of the bends and the lazarette for leprosy patients – among other details.

“All the gardens and cleaning outside were done by prisoners [from the nearby Long Bay Jail],” she says. “They wore white uniforms with numbers on their back. All the bread used by the hospital was baked at Long Bay Jail.

“I saw two girls who were polio victims on the iron lung. The first kidney transplant in New South Wales, and I think Australia, I nursed her…

“You had to [slip her food through the door] under purple light; and gown up and be quite sterile to go in.”

Towards the end of her training, Sandra returned to the country and to familiar nursing traditions, including a regimented private life.

“We paid board and got fed, three meals a day,” Sandra recalls.

“The sisters had their own table to sit at and so did the matron. When the matron walked into the dining room, everyone stood up and put their hands behind the back. When she sat down, you sat back down again.”

Sandra still found the pluck to ask the local hospital board whether she could marry the love of her life.

“Because nurses couldn’t be married when I trained,” she explains. “You had to get permission. You still had to live in the nurses’ home, where we all lived, and could only go home to be with your husband on your days off.”

As the ring slid onto her finger, her hair unfurled from the veil. The 70s were dawning and the Australian nursing sector was becoming secular and centralised.

“Slowly, a lot of the hospitals gave up their nursing training; that was when education of nurses at university started,” Sandra remembers.

“Lots of the buildings were converted… I went back and did a diploma at what became Charles Sturt University – and [later] a Bachelor of Health Science, and one for mental health as well.”

She remembers the early days of the “milk run” when the state ambulance service’s first two planes – “Alpha Mike Goff” and “Alpha Mike Bravo” – started landing in Wagga Wagga every Monday and Thursday to retrieve patients to Sydney.

These early signs that technology would revolutionise healthcare continued to fulfil their promise years later when computers appeared on the ward. At larger hospitals, Sandra had to adapt to unfamiliar tech, but

it was in the rural hospitals – where admin staff clocked off at 5pm – where the need for computing skills was greatest.

Then suddenly, for a few wild days, the healthcare industry’s growing dependency on computers poised to backfire. Gen Y and Z readers may be too young to remember the Y2K scare.

“I was on night shift at the high-dependency ward with 12 patients when they changed from the 1990s to the 2000s,” Sandra says, “Just myself and another RN. All the executives were upstairs. The bosses, admin staff, IT staff – like buzzy bees.

“We had two large wooden doors you came through to get to our ward, out of the stairwell or lift. Oh, the anticipation, that someone would open the door, come rushing in and say: ‘you’ve got to do this, you’ve got to evacuate!’

“But nothing happened. The phones never got disconnected; the computers just rolled over, never shut down. About 4am, everyone packed up and went home. It was the year 2000.”

Throughout her career, Sandra found her passion for aged care growing and of all her career achievements, she’s most proud of her advocacy in this space.

“Some of the older members of our community had said ‘everything is done for the young – football, tennis, golf – all done for the young people. Nothing here for the oldies. We keep getting pushed aside’,” she says.

“Having a nursing background in a hostel and nursing home, and retirement village management, I had a bit of an idea about that and thought ‘let’s go for it, give it our best shot’.

“I got together with that community of 500 people and we formed a committee to raise money to build aged care units for the socially disadvantaged in town. With contacts I had with an architect, he drew up plans, and we started to fundraise.

“As the money came in and the momentum grew, the support increased. With a grant from the Commonwealth, we built the first two units. People of the town and district could see it was going to happen.

“When I left there, we had built five units, using one and a quarter million dollars in grants. I’ve had lots of opportunities, being a nurse – and not all of them in hospitals.”

Reflecting on a career that has also included working in prison health and as a DON, Sandra says there is no secret behind her 60 years of nursing (that or she won’t tell us). She does, however, have a few closing reflections as she bids farewell to scrubs.

“Accept everyone you care for,” she advises.

“There are times when they frustrate you and are doing the wrong thing and you have to be firm, but you can still treat them as a human being, politely and with empathy. If you can treat everyone like you want your mother and father treated, then I think you’ve done very well.

“The camaraderie, the friendships, the people I’ve met, the advances of medicine and surgery – how wonderful to have gotten to now and see what I’ve seen. Will someone [who is starting out now] have that opportunity to see as much?”

Interested in sharing your experience of working in remote health? Perhaps there is a topic that you would like to see covered in the CRANAplus Magazine? Get in touch with your story or suggestion at communications@CRANAplus.org.au