“In a country like Australia, we should be doing more,” she says. Trachoma, the leading cause of preventable blindness in the world, is completely preventable itself. “We are the only developed country where trachoma is endemic.” Almost all cases occur in Aboriginal people in remote desert communities.

In Western Australia, the state with the poorest statistics in the country according to world-leading medical organisation the Kirby Institute, there are around 40 communities listed as at risk.

The four regions of the Goldfields, Pilbara, Central Desert and Midwest is the focus for the project and Melissa, who has devoted herself to the fields of public and environmental health for more than 30 years, is heartened that in the Pilbara, for example, cases are beginning to reduce.

The disease is strongly associated with non-functional health hardware and poor hygiene in people’s homes.

That’s where Melissa, research officer Scott MacKenzie, and the band of Environmental Health Workers (EHWs) steps in. Their aim is to reduce the risk factors in the home, providing on the ground assistance to make sure families have the means to be able to wash themselves and their clothes and follow the health promotion messages around stopping germs.

“It’s all well and good to tell people to shower daily, wash their hands and wash their blankets regularly, but it’s not easy to carry out if the showerhead is missing, the tap doesn’t work, drains are blocked and the washing machine is too small to fit in a bulky blanket,” says Melissa.

“We couldn’t do what we do without the local Environmental Health Workers.

“They are critical to the success of the project.” Their role in communities in the past was to carry out tasks such as mowing lawns.

No more, she says. After undergoing Certificate II basic training, the duties for the band of EHWs include undertaking home audits, carrying out emergency plumbing jobs and providing a key link to help families secure the practical help they need from other agencies.

A recent report shows that, in the past 12 months, the #endingtrachoma team together with EHWs identified 455 issues for families. This resulted in 213 plumbing fixes and 399 issues reported to housing. “Those statistics are only when we work together… so the numbers are much higher when you add what the EHWs do when we are not in community with them!” Melisa points out.

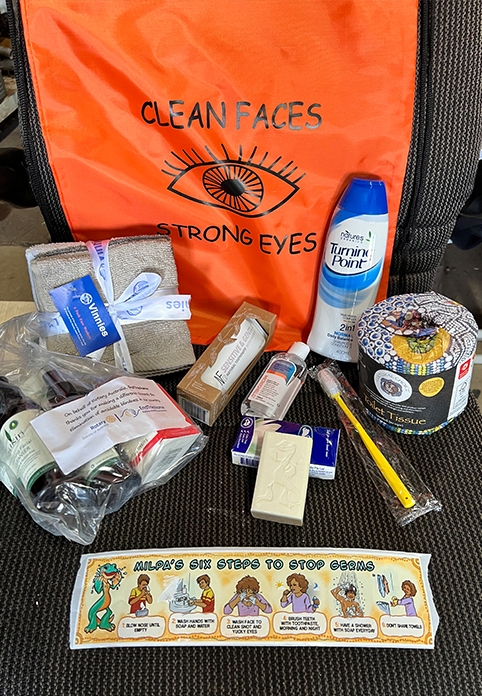

The team also hands out hygiene kits, including items such as soap and coloured towels and light bulbs, and promotional material with the key messages. “And we go back every 3–4 months,” says Melissa, “as we all know that continuity is so important to get the messages across.

“When we visit, we do a whole community in one week, which cost-effectively bulks the repairs together and ensures there are no issues of blame or shame.”

“I’m a doer,” says Melissa, Senior Research Fellow with the Institute since its inception in 2008, who loves nothing better than driving into a community with the washer/drier combos on a trailer, complete with a BBQ and a jumping castle to turn the visit into a family community event.

In a recent visit, one of the environmental health teams in the Pilbara did 38 loads of blankets in one community alone.

These whitegoods are thanks to Rotary’s Australia-wide EndTrachoma programme aimed at helping to eliminate trachoma in Australia. Rotary also funds the hygiene kits.

The PHAI which auspices the trachoma project has received funding recently to auspice another project to focus on the food security and kitchens in remote Aboriginal communities, asking families what equipment they want and need in their house to enable safe and healthy food storage and cooking, and Melissa is looking forward to working in tandem with that project.

Collaboration, whether it’s support from organisations such as Rotary, working along with other research projects and professionals in other services such as education and health is the answer to speeding up that process of eliminating trachoma in Australia, says Melissa.

With funding for the Environmental Health Trachoma Project set to end in July 2025, Melissa said it was important to continue to focus on the home.

“This is critical to prevent trachoma so additional funding to keep the project running longer would be great,” she said. “I would also like to see more connections with the development of a national Healthy Homes project.

“We would also like to encourage more collaboration with the teams that address other diseases related to the home such as rheumatic heart diseases and scabies so we can share expertise, ideas and funding.”

There have been massive attitude changes in the five years since this project began, says Melissa, with government bodies accepting that a house is more than an asset, it’s a place to feel comfortable, healthy and safe.

And in the spirit of holistic care, Melissa welcomes clinicians in the communities they visit to go with the #endingtrachoma team on visits to homes. There they see firsthand what is required to close the gap between the health and hygiene messages they give to patients and what’s needed to make sure families can follow those guidelines.