This site may not work properly using older versions of Edge and Internet Explorer. You should upgrade your browser to the latest Chrome, Firefox, Edge, Safari, or any other modern browser of your choice. Click here for more information.

Your Stories

This is where we tell your stories, cover topical issues and promote meaningful initiatives.

The History of CRANAplus (Part 3): The fight for identity — validating RAN practice

How can you make your voice heard when you are out of sight from the majority of Australians? CRANA would answer this question successfully, but not without difficulty, over the next four decades. As Jenny Klotz put it in 1985, “The Tyranny of Distance is a daunting factor in trying to achieve any goals for an organisation such as CRANA.”

“However, [distance] is also our most saleable asset,” she continued. “Aside from the fact that the press at large is more interested in the gore, horror and extremes faced by Remote Area Nurses, I feel that we as an organisation are just beginning to tap into a huge public and political empathy for the work we perform.”

To establish this empathy for the profession, CRANA realised that it would need to develop a set of standards outlining the unique skill set required by remote area nurses. Despite its efforts, it would sometimes take a widely publicised traumatic event to catalyse change.

The need for standards

While the campaign for education was going on, a concurrent campaign to develop remote area nursing standards was also underway.

Excellent work was being done by RANs but how could one know it was excellent work, without standards? And if a RAN or a health service had room to grow, how could they assess themselves and know what to aim for?

The issue was pronounced for RANs, who outside of the CRANA conference had limited opportunity to interact with peers, meaning that even ‘informal’, socialised standards were sometimes missing.

In 1986, CRANA convened its first subcommittee to develop standards. Committee convener, Angela Low, summarised the challenges they faced:

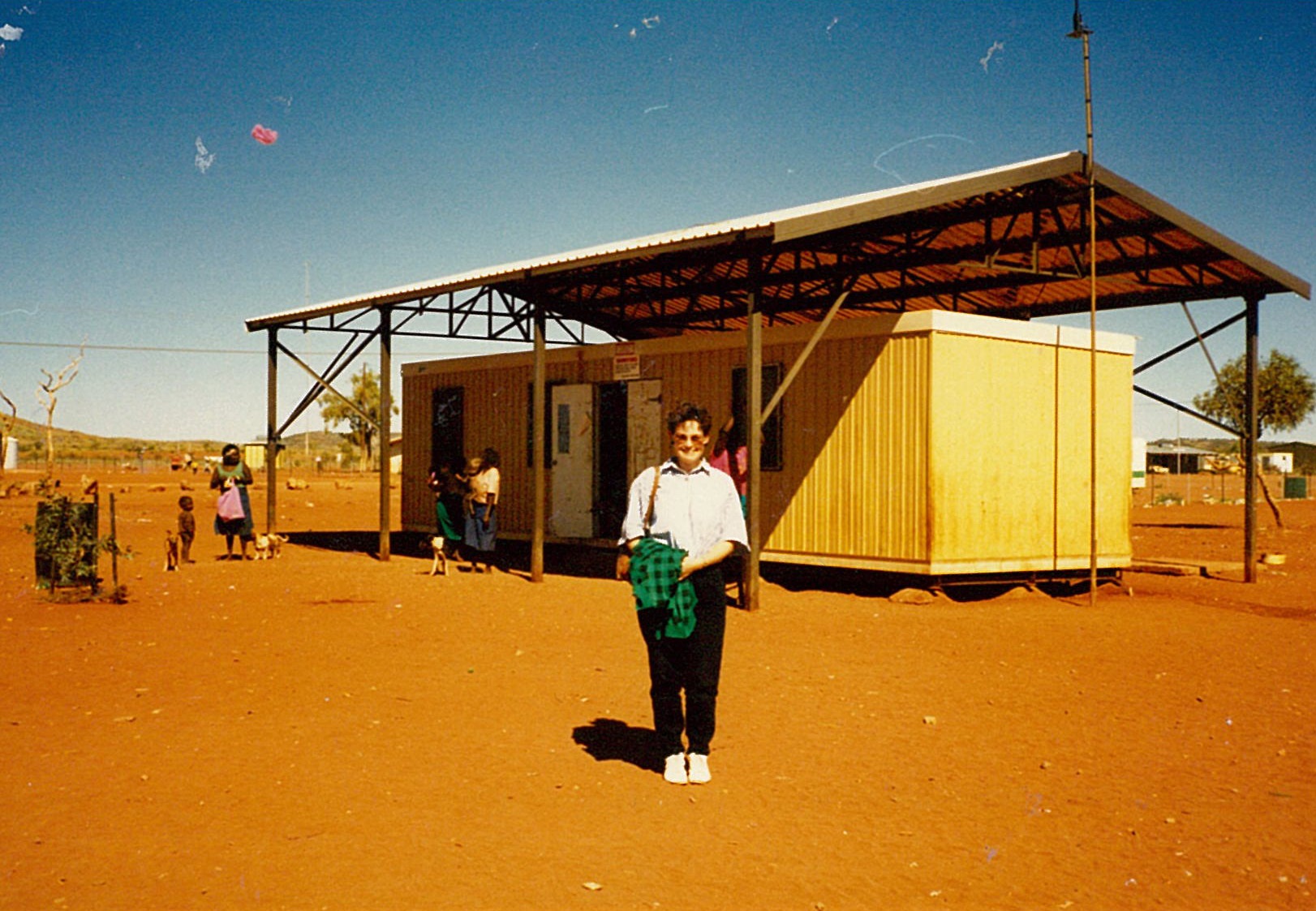

“How could nurses from such a diversity of back- grounds from Aboriginal Communities of Arnhem Land and the centre, to company and prospector mining towns, to the deserts of the centre and the west and the snow fields of the south, and even the islands of the Indian Ocean, explain to the profession at large the elements of their role they all instinctively felt they had in common. Further, how could they convince their colleagues that despite this diversity they were a unique entity that has special needs and responsibilities which often, of necessity, went beyond the accepted bounds of nursing practice?”

The subcommittee felt a heightened sense of urgency in the late 1980s. A young English nurse, Sophie Heathcote, had been sent to work in remote New South Wales. There was an incident with a tragic outcome. A young man died. What followed included a series of investigations and inquiries, and Sophie was temporarily deregistered.

CRANA believed that Sophie had been unfairly made into a scapegoat and at the 1989 CRANA conference, remote area nurses signed a petition for Sophie’s cause. In 1990, CRANA published its first remote area nursing standards which included its famous statement on the philosophy of remote area nursing. In 1991, Sophie’s appeal was upheld. She was later invited to speak of her experience at the CRANA conference¹. These two events marked a turning point in the national conversation. Suddenly, there was greater acknowledgement that RANs in the field were not being properly prepared or supported.

Continuing to push for standards

Throughout the next decade, CRANA continued to grow its representation on committees, including the budding National Rural Health Alliance and the Australian Pharmaceuticals Advisory Committee. As stated in a CRANA communiqué in 1996:

“Involvement in all of these groups marks a significant change in the public recognition by legislators of the ability of RANs to become involved in defining the rights and scope of their practice, if not self determining in this regard.”

Thanks in part to CRANA’s ongoing advocacy, the Federal Government invited tenders to develop competency standards for remote area nursing in 1997. A team of researchers with strong CRANA representation applied. Utilising CRANA’s network, this group consulted widely with RANs, consumers and others in the development of a nationally recognised set of competency standards for RANs. They envisioned that these new competencies, now funded, nationally recognised, and consistent, would give CRANA great strength to argue for the development of accreditation criteria and curricula designed to enhance remote practice.

These two themes – accreditation and curriculum development – define the legacy of the standards. The results were fast and instantaneous for curriculum development, in the form of CRANA’s postgraduate and Remote Emergency Care courses. The journey towards accreditation was to involve many more twists and turns, and is in many ways ongoing.

Advances and setbacks in recognition

In 2003, CRANA initiated its awards program, adding another string to its bow in the quest for professional recognition. CRANA’s Fellowship program was developed with similar goals in mind. Fellows were inducted to embody the standards of remote health practice and set an example in a largely self-regulating industry.

CRANA implemented initiatives like these with the ultimate goal of ensuring that nurses sent to remote areas were adequately prepared so that they could deliver high-quality, culturally safe care.

However, when the Northern Territory Intervention was announced in 2007, many feared that the progress made in this direction would come undone.

The Intervention followed the Little Children are Sacred Report and one of the measures it was to involve was compulsory child health checks. A fly-in, fly-out workforce, separate to existing primary health care arrangements, was to be created and include interstate staff.

CRANA was approached to be involved in preparing this workforce and it faced a challenging decision.

After discussing the matter with Aboriginal Medical Services Alliance Northern Territory (AMSANT), CRANA made the carefully controlled decision to proceed. As President Christopher Cliffe wrote at the time, “If

we are not involved then we would have no capacity to ensure that resources are appropriate and staff well prepared”.

Vicki Gordon, a CRANA Board Member in the 1990s and Remote Support Officer at this point in time, represented CRANA in the coordination and delivery of orientation to staff in Alice Springs and Darwin, working alongside paediatrician Dr Jim Thurley.

They were on the shortest of timeframes. Vicki began delivering ‘rapid briefings’ within nine working days of the announcements. On day 10, the first Child Health Check Team was deployed. Vicki in turn conducted the debriefs with returning staff.

“The Intervention had a huge negative impact on remote Aboriginal people, but CRANA thought ‘it’s happening and we need to make individual teams and people in community as safe as possible’,” Vicki reflects.

“It wasn’t something that CRANA would have ordinarily have done, but these were extraordinary times.”

Refreshing remote nursing standards

The National Registration and Accreditation Scheme was introduced in 2010. It aimed to ensure that all registered health professionals meet the same national standards, and to increase workforce mobility between states and territories. The Intervention was still front of mind for CRANA (by now known as CRANAplus), and sensing good will and opportunity for change, the organisation reignited its campaign for RAN standards.

Its own Remote National Standards and Credentialing Project commenced in 2012 and culminated in the endorsement of a new set of Professional Standards of Remote Practice: Nursing and Midwifery. CRANAplus aspired to make these standards user-friendly, contemporary, and reflective of the diverse practice areas under the remote and isolated banner.

Although then as now, nurses could be endorsed as Nurse Practitioners in a specialty relevant to remote practice, endorsement for RAN practice was not nationally consistent, available or recognised (for example, Rural and Isolated Practice [Scheduled Medicine] endorsement was only available to RNs in Victoria and Queensland). Therefore, CRANA set out to establish a nationally consistent credentialing process for the remote nursing and midwifery workforce – the RAN Certification Program. This involved a self and peer assessment to confirm that a remote area nurse met the minimum essential requirements to be a safe provider of remote health care.

However, as Angela Low from the Standards Subcommittee had intuited in 1990:

“[The value of standards is] limited unless employers and employing bodies acknowledge that they too have a role in maintaining a professional standard of remote area nursing practice.” CRANAplus promoted its up-to-date standards and engaged in conversations nationally to encourage employers and jurisdictions to embed them.”

This campaign brought about significant local successes, but overall, its success was mixed.

CRANAplus does not currently offer the RAN Certification Program, but has been actively involved in the next chapter of remote area nursing standards. The organisation recently participated on the steering committee for The National Rural and Remote Nursing Generalist Framework 2023 – 2027, convened by the Office of the National Rural Health Commissioner.

This document describes the unique context of practice and core capabilities for rural and remote RN practice. As with the landmark documents that have gone before it, its potential to bring about change is palpable. In fact, the remote health sector is poised at a critical moment. The extent of implementation is set to be the decisive factor.

“The Framework provides nurses with a tool for self-assessment, enabling them to work meaningfully with educators and mentors to build their capabilities,” outgoing CEO Katherine Isbister said in March.

“Importantly, the Framework is also a tool that employers, educators, governments, and peak bodies can use to assess their cur rent programs, consider scope of practice and tailor their professional development opportunities. The Framework is a meaningful step towards a structured and widely available remote area nursing pathway, on par with the rural generalist path ways for medicine and allied health.”

CONTINUE THE HISTORY

Footnotes

- Sophie says that “the fact that CRANA reached out and found me is something that has always stayed in my heart” and that it inspired her Presidency of the Board in the 2000s. This gave her a platform to promote the need for education and preparation. She is now a CRANAplus Fellow.